In the first of my two-part exploration into the intricacies of compression, I outlined and described the core elements of the humble compressor unit itself. Once these essential controls have been fully understood, the compressor becomes one of your most trusted and useful tools with regard to the art of mixing and music production in general. In this, the concluding section of the series, I want to delve into practical applications of compression within a musical context - 3 applications to be precise, including the use of a compressor on a single instrumental track, summed bus track and the master bus track.

These 3 uses of compression all share one important factor in common - transparency. In other words, we don't want to be able to hear the actual operation of the compressor itself, only the beneficial results of its effect on the sound or sounds being processed. This is precisely why the relationship between compressor settings and the audio material itself is so vital and will be referred to continually throughout our discussion - the former can not operate effectively without carefully consideration of the latter.

I hope to sufficiently cover each technique to the point where you'll be able to start using them in your productions straight away, so let's get right to it - first up, I'd like to talk about placing a compressor on a single instrumental track.

Track Compression

As we're only dealing with a single sound such as a synth, vocal or bass part, we can really concentrate the functioning of the compressor towards one result. Before you start tweaking those dials however, it's very important to consider the nature of the material you'll be passing through the compressor first - is it full of lots of snappy transients' Does it take a long time to decay' Is the dynamic range especially large' As with the majority of audio processing decision-making, it pays dividends to sit and listen through to things before beginning, making yourself familiar with the general feel of the sound you want to affect and then applying processing.

As a rough rule-of-thumb, a sound that is dynamically busy (featuring lots of quick changes from loud to quiet) will require a sharp, fast response from your compressor and those that take longer to change in loudness will suit slower response times. For sounds with slow, evolving attacks such as pads or sub basses, think 50ms attack times and far beyond. Conversely, sounds that are very transient-heavy, such as drums, will need faster settings but be careful not to squash those delicate initial transients! I like to begin at around 20-30ms and work from there for just such percussive sounds.

Release settings can be trickier to nail and the results of which, as with attack, will become more apparent in direct proportion to the amount of work your compressor is doing. For sounds with long decays, higher settings are where to begin experimenting - around 75ms and beyond - as this will allow the compressor to gently ease in and out of its processing cycle as the sound crosses its threshold and back. Quicker sounds with shorter decays will call for correspondingly quicker release times - I'd start at around 50ms for drums - but often slightly overcompensating on release time can produce a smoother, more transparent result. For example, you might be compressing drums with quick, 20ms decays but using a release setting of 30ms would typically sound smoother than exactly matching the length of the note decays themselves.

The Big Hitters: Threshold, Make-up Gain & Ratio

Before adjusting your main threshold, make-up gain and ratio settings, you'll want to consider just how much compression you want to apply and the nature of compression required. For example, if you have a sound that stays relatively consistent in volume with only occasional spikes, such as a slapped bassline, you'll likely want to set a high ratio (e.g. 3:1 and much higher) as well as a fairly high threshold value (e.g. around -6dB). Basically, you want to set the threshold to the point where the compressor is only triggered during the slaps and volume spikes, and the ratio so that the compressor works hard to pull the spikes right back in volume. For less dynamically spiky sounds, lower threshold and ratio settings will probably be the order of the day.

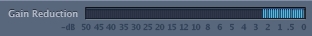

It's important to always pay attention to the gain reduction meter when applying compression - this is your guide to when the compressor is at work and when it is idle, as well as how much it is working at any given point. I almost never apply more make-up gain than the value of gain being reduced, as this keeps sounds from peaking. In fact, applying too much gain can even produce a lumpy result, which is usually the opposite of what a compressor is being employed to achieve!

Unless you want a seriously over-compressed result, such as that exemplified by the ultra-thick sound made famous in French House tunes around the turn of the 21st century, you'll want the gain reduction meter to return to 0dB at least occasionally as your sound plays. This should ensure your sound will retain some of its natural dynamic character and internal life - a pivotal element in the expressive power of recorded music.

Bus Compression

Another important application of compression is on a bus track of summed signals, such as a collection of drum sounds feeding into a drum bus channel or several bass sounds combining on a bus track. Here, the compressor's job is much more about cohesion and getting the disparate sounds feeding into the bus track to sound as one single unit of audio. It is when performing this function that compressors are typically referred to as the 'glue' in a mix, such is their ability to gel and blend sounds together seamlessly.

Perhaps the most important thing to remember when using a compressor on your bus tracks is that the compressor is affecting every element feeding into the bus - this is even more important in relation to the master bus, as we'll discuss further below. The knock-on effect of this is that your choices of attack, release, threshold, make-up gain and ratio settings must adequately accommodate a range of signals, rather than only one as with our previous, single instrumental track example. Often, this means using more relaxed settings than you would with a single track compressor - the 'gluing' effect of the bus compressor is sometimes able to shine from no more than 2 or 3 dB of gain reduction for example. So, you might want to begin by dialling in a pretty high threshold value (-10 dB and up) alongside a lower ratio (between 1.2-2:1) - watch your gain reduction meter and you should start to hear that gluing effect coming into play with only gentle flickerings of the meter into action and back.

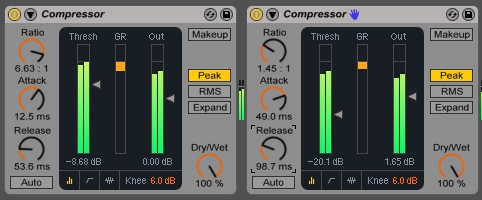

Another trick I like to use particularly on the drum bus is loading up two compressors in series. Obviously, you should be sure you have justifiable and separate reasons for loading up more than one compressor on any track but the reason that this technique often works for drums, is that the first can be used to tame lumpy volume peaks and the second can be used for the gluing purpose just described. It would be very tricky, of not impossible for a quality compressor, to perform both functions at the same time so the use of two compressors splits the processing responsibility. You might think that introducing another compressor increases the risk of rendering the operation of the compressors audible but, if used subtly, the reverse is in fact true - decreasing the workload for each compressor means each can add a subtle change to the sound running through them, rather than one plugin having to work overtime to fulfil multiple functions.

Master Bus Compression

The final application of compression I want to look at here is on the master bus track. As with the previous bus track example, it is vital to remember that any processing applied to the master bus will affect every single sound in your track, so subtlety is king here.

Master bus compression is usually about either one of two things, which can be used separately or simultaneously - gluing and increasing loudness. Much like the master bus example, we can use an even subtler amount of compression to gently bring the separate elements of our track together sonically (even 1dB of gain reduction might be all that you need to hear this taking effect). Opto compression models are nice to work with in this context because they're a bit slower to react than other circuit types, such as VCA for FET, meaning they have less of an intrusive effect on transients. Other models and compression types can work equally well but I'd simply stress to begin with subtlety, using high threshold settings and low ratios.

If you're going to master your track, you might not want to use compression on your master bus to achieve extra loudness and leave this to the mastering stage. However, if you find your track lacking in volume or want to create a more radio or release-friendly mix without mastering, you can use compression on your master bus to squeeze all the signal amplitudes in your track as one. It is going to be very difficult to use a compressor transparently in this way, so again, less is more but you might achieve better, less obvious results with fast-response compressors such as VCAs.

A final trick I sometimes use to achieve an extra degree of warmth with my tracks is to actually push the master bus compressor into clipping (i.e. over 0dB) and allowing a limiter to round off the peaks. This involves simply setting the make-up gain to a slightly higher value than what the compressor is reducing - it is important to experiment with different limiters here however as whether you get a nice, warm, soft-saturation effect or gurgling distortion will be reliant on the limiter's peak reduction algorithm or circuit. Certain limiters actually have switchable circuit types that allow for this sort of subtle driving of a hot signal, so give them a shot and see what works for your track.

Compression Conclusion

This brings my Compression 101 series to a close - I hope you've found the discussion interesting and useful, and you can see a way to incorporate some of the techniques outlined above in your productions. If anything, I hope the tutorials have increased your awareness of the functions and functionality of the humble compressor and shown you that, alongside EQ, compression is a music producer's best friend!