Welcome to my new series delving into the secrets of electronic music production, shedding light on some of the more shadowy tricks seasoned producers lean on to make their music bang!

For my first entry, I’d like to explore the wonderful world of parallel chords, something entire genres such as House and Techno simply couldn’t live without.

Their use isn’t just limited to the dancefloor however, as these babies have found their way into mainstream musical culture and beyond. We’ll start with a brief history lesson, before plunging head-first into the why and the how of the parallel chord progression.

Be sure to stick around till the end of the article, as there might just be some free sounds in it for you - all set? Let’s dive in!

Sinewaves & Samples

In the beginning, there was a drum machine. It was called the Roland TR-808, and whilst it might have initially been created to accompany practising amateur musicians, it was quickly championed by DJs and producers to help fuel the burgeoning House and Techno scenes in mid to late 80s America.

The punch and low-end boom of the unit was a perfect recipe for playing out to crowds in large clubs but rhythm alone was of course not enough to keep dancers transfixed - for the melodic elements of their music, producers turned to analog synths and the humble sampler to cook up simple but powerful basslines, leads and chord sequences.

Thus, samples of chords as performed on a wide variety of instruments could be captured via sampling from records for playback and sequencing, accompanying pounding drum machine rhythms to intoxicating effect.

Sampling technology at the time limited recordings to just a few seconds in length and, given the fact producers were only able to work with chords present in pre-existing recordings, typically resulted in single chord samples, or ‘stabs’, being played back at different pitches to create simple sequences or chord progressions.

Anatomy Of A Chord

Before moving on, let’s introduce a little theory and a basic definition of a chord - a chord is any group of notes that are played together and thus to be treated as a distinct whole i.e. a C major triad consists of 3 notes, C, E and G, which are all played at the same time and should be perceived as a single musical event or entity.

In traditional Western classical music, which also informs popular styles and genres, chords relate to scales, which follow prescriptive rules as to which ‘flavour’ or type of chord should be played given the root note. For example, in the key of C major, if you wanted to create a chord progression moving from C to A, you would play a C major chord followed by an A minor chord.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to explain just exactly why this is, but if you’ve grown up amidst Western musical traditions it’s safe to say that you will be very familiar with the most central of these rules on an intuitive level, simply from being exposed to so much music that follows them.

Now, whether by design or as a result of the limitations of the technology used in creating the music, House and Techno often ignore these rules.

In the example above, we learned that the rules state that you should move from C major to A minor if you’re in the key of C major - however, the pioneers of Dance music often didn’t have the luxury of being able to choose the flavour of the chords they were sequencing, as all they had to work with was a single chord sample.

So, following the same example, say we have a sample of a C major chord - we can pitch this chord down 3 semitones to give us an A chord, but it won’t be A minor, it will be A major. Similarly, if we want to pitch it up 4 semitones to an E, which according to the rules should be E minor, again we only have the major chord type to work with!

No matter how we pitch the sample around, the flavour or tonality will always be the same - and so it was that parallel chords came to be a hallmark of early electronic Dance music, and whilst the technology has evolved far beyond the limitations of the late 80s, parallel chords are still heard and celebrated in today’s biggest Dance tunes.

Building Your Own Progressions

Here’s an example of a famous parallel chord progression from Techno forefather Kevin Saunderson’s Inner City project, featuring in the undisputed classic ‘Good Life’:

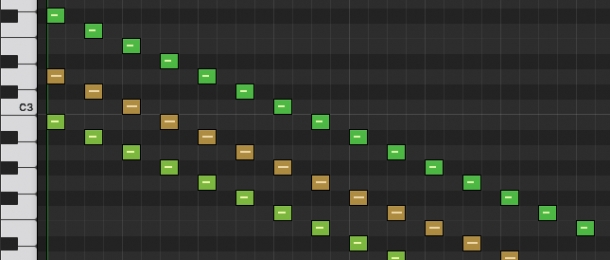

The chord progression, heard through the entire track, consists of 4 parallel minor chords: Bm, F#m, Am and Em, which looks like this in Logic Pro X's piano roll:

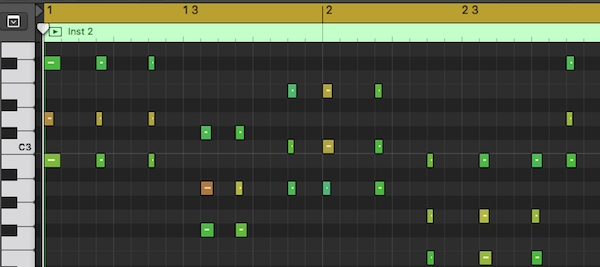

If this progression was to follow the rules of Western classical tonality, the chords would be Bm, F# major, A major and Em, looking like this (changed notes highlighted):

So, according to the rules of traditional Western harmony at least, 2 of the chords in Saunderson’s progression are incorrect - however, try switching out the two middle minor chords for their major counterparts and the sequence quickly loses a lot of its character and vibe!

I’ve whipped up a quick example loop to showcase the difference, simplifying the original rhythm quite a bit - here are the two versions of the chord progression, side by side:

Now I don’t know about you but to me the first version, the one actually used in the Inner City tune, just has a meaner, more interesting vibe to it - it has more character in other words. There’s something about the repeated minor tonality that just hammers home the mood of the notes and synth sound with greater effect than the ‘corrected’ version - I’ll let you be your own judge though!

I’m sure a proper music theorist could conjure up any number of clever reasons as to why this progression still sounds so good despite ignoring such fundamental rules, but my own feeling is that keeping chord tonality consistent actually more closely aligns these parallel sequences to the essential principles of House, Techno and other Dance genres - namely the stripping back of arrangements to key ingredients, coupled with a major shift in focus from harmony to rhythm.

There are countless examples of parallel chord progressions scattered throughout the history of House and Techno, and the basic method of sequencing a single chord across different pitches works with pretty much any type or flavour you care to try it with - some of my favourites are major 7ths, minor 4ths and suspended 4ths, but really the sky is the limit here so get experimenting.

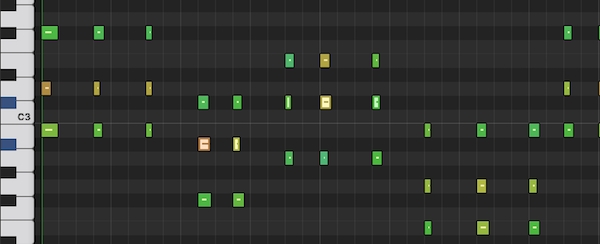

Here are three quick examples, both built from a single chord - the first is a simple minor triad:

The second is made using a jazzier major 7th chord:

As a final demo, here’s the same sequencer pattern used in the previous example, but this time triggering a patch from our Detroit Chords - Synth Samples & Patches pack:

I hope you’re getting a feel for how quickly and easily satisfying chord progressions can be built up in this way - you only have to choose a single chord to get going!

To help you with your initial experiments, I’ve made a selection of 50 free chord stab samples available for you to download below including the sounds heard in the first 2 demos above, which was originally made exclusively available to those signed up to our newsletter team (you can join as well using the box at the very bottom of this page).

The sounds have been taken from across the ModeAudio catalogue of loops and samples and include snippets of guitars, synths and even some noise, so just load them into your favourite soft sampler and start bashing those keys to make your own progressions.

Of course, you don't have to restrict your use of parallel chords to just sampling - programming MIDI sequences with soft synths is much more flexible, provided your synth is polyphonic, or you can even go as far as to create parallel chord presets if your synth has multiple oscillators. Our Unwind - Serum Chord Presets release offers exactly this, across 50 custom patches.

Happy experimenting and until next time, get creative!